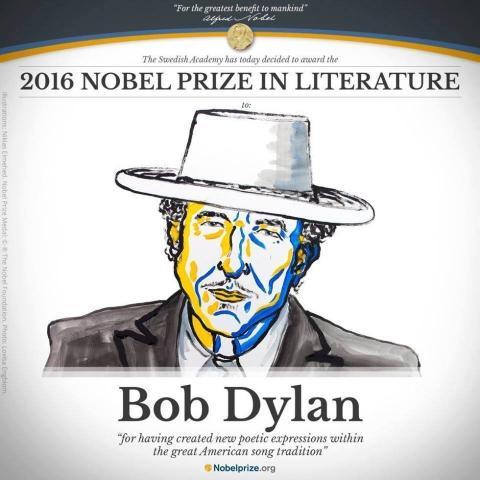

Nobel Day Transcripts: Banquet Speech and Presentation Speech - © The Nobel Foundation 2016

BANQUET SPEECH by Bob Dylan given by the United States Ambassador to Sweden Azita Raji, at the Nobel Banquet, 10 December 2016.

Good evening, everyone. I extend my warmest greetings to the members of the Swedish Academy and to all of the other distinguished guests in attendance tonight.

I'm sorry I can't be with you in person, but please know that I am most definitely with you in spirit and honored to be receiving such a prestigious prize. Being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature is something I never could have imagined or seen coming. From an early age, I've been familiar with and reading and absorbing the works of those who were deemed worthy of such a distinction: Kipling, Shaw, Thomas Mann, Pearl Buck, Albert Camus, Hemingway. These giants of literature whose works are taught in the schoolroom, housed in libraries around the world and spoken of in reverent tones have always made a deep impression. That I now join the names on such a list is truly beyond words.

I don't know if these men and women ever thought of the Nobel honor for themselves, but I suppose that anyone writing a book, or a poem, or a play anywhere in the world might harbor that secret dream deep down inside. It's probably buried so deep that they don't even know it's there.

If someone had ever told me that I had the slightest chance of winning the Nobel Prize, I would have to think that I'd have about the same odds as standing on the moon. In fact, during the year I was born and for a few years after, there wasn't anyone in the world who was considered good enough to win this Nobel Prize. So, I recognize that I am in very rare company, to say the least.

I was out on the road when I received this surprising news, and it took me more than a few minutes to properly process it. I began to think about William Shakespeare, the great literary figure. I would reckon he thought of himself as a dramatist. The thought that he was writing literature couldn't have entered his head. His words were written for the stage. Meant to be spoken not read. When he was writing Hamlet, I'm sure he was thinking about a lot of different things: "Who're the right actors for these roles?" "How should this be staged?" "Do I really want to set this in Denmark?" His creative vision and ambitions were no doubt at the forefront of his mind, but there were also more mundane matters to consider and deal with. "Is the financing in place?" "Are there enough good seats for my patrons?" "Where am I going to get a human skull?" I would bet that the farthest thing from Shakespeare's mind was the question "Is this literature?"

When I started writing songs as a teenager, and even as I started to achieve some renown for my abilities, my aspirations for these songs only went so far. I thought they could be heard in coffee houses or bars, maybe later in places like Carnegie Hall, the London Palladium. If I was really dreaming big, maybe I could imagine getting to make a record and then hearing my songs on the radio. That was really the big prize in my mind. Making records and hearing your songs on the radio meant that you were reaching a big audience and that you might get to keep doing what you had set out to do.

Well, I've been doing what I set out to do for a long time, now. I've made dozens of records and played thousands of concerts all around the world. But it's my songs that are at the vital center of almost everything I do. They seemed to have found a place in the lives of many people throughout many different cultures and I'm grateful for that.

But there's one thing I must say. As a performer I've played for 50,000 people and I've played for 50 people and I can tell you that it is harder to play for 50 people. 50,000 people have a singular persona, not so with 50. Each person has an individual, separate identity, a world unto themselves. They can perceive things more clearly. Your honesty and how it relates to the depth of your talent is tried. The fact that the Nobel committee is so small is not lost on me.

But, like Shakespeare, I too am often occupied with the pursuit of my creative endeavors and dealing with all aspects of life's mundane matters. "Who are the best musicians for these songs?" "Am I recording in the right studio?" "Is this song in the right key?" Some things never change, even in 400 years.

Not once have I ever had the time to ask myself, "Are my songs literature?"

So, I do thank the Swedish Academy, both for taking the time to consider that very question, and, ultimately, for providing such a wonderful answer.

My best wishes to you all,

Bob Dylan

© The Nobel Foundation 2016

General permission is granted for immediate publication in editorial contexts, in print or online, in any language within two weeks of December 10, 2016. Thereafter, any publication requires the consent of the Nobel Foundation. On all publications in full or in major parts the above copyright notice must be applied.

PRESENTATION SPEECH by Professor Horace Engdahl, Member of the Swedish Academy, Member of the Nobel Committee for Literature, 10 December 2016.

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Your Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen,

What brings about the great shifts in the world of literature? Often it is when someone seizes upon a simple, overlooked form, discounted as art in the higher sense, and makes it mutate. Thus, at one point, emerged the modern novel from anecdote and letter, thus arose drama in a new age from high jinx on planks placed on barrels in a marketplace, thus songs in the vernacular dethroned learned Latin poetry, thus too did La Fontaine take animal fables and Hans Christian Andersen fairy tales from the nursery to Parnassian heights. Each time this occurs, our idea of literature changes.

In itself, it ought not to be a sensation that a singer/songwriter now stands recipient of the literary Nobel Prize. In a distant past, all poetry was sung or tunefully recited, poets were rhapsodes, bards, troubadours; 'lyrics' comes from 'lyre'. But what Bob Dylan did was not to return to the Greeks or the Provençals. Instead, he dedicated himself body and soul to 20th century American popular music, the kind played on radio stations and gramophone records for ordinary people, white and black: protest songs, country, blues, early rock, gospel, mainstream music. He listened day and night, testing the stuff on his instruments, trying to learn. But when he started to write similar songs, they came out differently. In his hands, the material changed. From what he discovered in heirloom and scrap, in banal rhyme and quick wit, in curses and pious prayers, sweet nothings and crude jokes, he panned poetry gold, whether on purpose or by accident is irrelevant; all creativity begins in imitation.

Even after fifty years of uninterrupted exposure, we are yet to absorb music's equivalent of the fable's Flying Dutchman. He makes good rhymes, said a critic, explaining greatness. And it is true. His rhyming is an alchemical substance that dissolves contexts to create new ones, scarcely containable by the human brain. It was a shock. With the public expecting poppy folk songs, there stood a young man with a guitar, fusing the languages of the street and the bible into a compound that would have made the end of the world seem a superfluous replay. At the same time, he sang of love with a power of conviction everyone wants to own. All of a sudden, much of the bookish poetry in our world felt anaemic, and the routine song lyrics his colleagues continued to write were like old-fashioned gunpowder following the invention of dynamite. Soon, people stopped comparing him to Woody Guthrie and Hank Williams and turned instead to Blake, Rimbaud, Whitman, Shakespeare.

In the most unlikely setting of all - the commercial gramophone record - he gave back to the language of poetry its elevated style, lost since the Romantics. Not to sing of eternities, but to speak of what was happening around us. As if the oracle of Delphi were reading the evening news.

Recognising that revolution by awarding Bob Dylan the Nobel Prize was a decision that seemed daring only beforehand and already seems obvious. But does he get the prize for upsetting the system of literature? Not really. There is a simpler explanation, one that we share with all those who stand with beating hearts in front of the stage at one of the venues on his never-ending tour, waiting for that magical voice. Chamfort made the observation that when a master such as La Fontaine appears, the hierarchy of genres - the estimation of what is great and small, high and low in literature - is nullified. “What matter the rank of a work when its beauty is of the highest rank?" he wrote. That is the straight answer to the question of how Bob Dylan belongs in literature: as the beauty of his songs is of the highest rank.

By means of his oeuvre, Bob Dylan has changed our idea of what poetry can be and how it can work. He is a singer worthy of a place beside the Greeks' ἀοιδόι, beside Ovid, beside the Romantic visionaries, beside the kings and queens of the Blues, beside the forgotten masters of brilliant standards. If people in the literary world groan, one must remind them that the gods don't write, they dance and they sing. The good wishes of the Swedish Academy follow Mr. Dylan on his way to coming bandstands.

© The Nobel Foundation 2016

General permission is granted for immediate publication in editorial contexts, in print or online, in any language within two weeks of December 10, 2016. Thereafter, any publication requires the consent of the Nobel Foundation. On all publications in full or in major parts the above copyright notice must be applied.