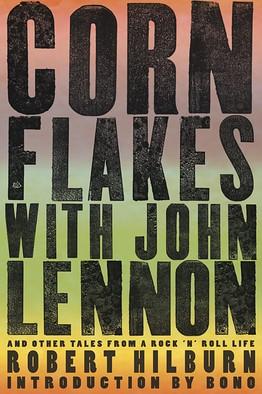

November 2009 - Cornflakes with John Lennon

Robert Hilburn was the pop music critic and editor at the L.A. Times from 1970 to 2005. He describes his new book, Corn Flakes with John Lennon as “a highly opinioned and deeply personal memoir which focuses on my relationships with and thoughts on many of the most important and inspiring artists in rock -- artists who not only helped build rock as an art form but whose craft and commentary helped shape the social values of our times: Elvis Presley and John Lennon, Bob Dylan and Janis Joplin, Johnny Cash and Stevie Wonder, Bruce Springsteen and U2, Phil Spector and Michael Jackson, Public Enemy and N.W.A and Kurt Cobain and Jack White. ” We had the pleasure of interviewing Mr. Hilburn about his experiences interviewing and writing about Bob Dylan and others over the years. We ran a contest to win a copy of the book, asking fan club members to submit questions they would like Mr. Hilburn to answer. Enjoy the interview, visit Robert Hilburn's website (www.roberthilburnonline.com) and purchase your copy of Corn Flakes with Lennon here: http://www.indiebound.org/book/9781594869211 ,

here: http://www.amazon.com/Cornflakes-John-Lennon-Other-Tales/dp/1594869219

or at your local independent bookstore!

BDFC:

Our website focuses on elements of Bob's music and artistry that he talked about as important when we met him. One of these things is his live performance, and in f act in the book you quote him about the importance of live performance saying, “…you're either a player or you're not a player . . . if you just go out every three years or so, like I was doing for a while, you lose touch.” As a historian of his music, can you comment on how you view Bob's live performance as part of his legacy? What do you think will be the most remembered aspects of Bob's legacy as a live performer?

RH:

First, let me say I don't in any way want to give the impression I am speaking for Bob Dylan or representing any private feelings he shared with me. I respect him too much to want to ever imply I am speaking for him. These are solely my thoughts.

To me, Bob Dylan sees himself as part of a troubadour tradition that stretches back beyond such major influences as Woody Guthrie, Charlie Patton and Hank Williams. I get the sense that he thinks his “job” is to write songs and then perform them for people night after night—spreading the gospel, if you will, to all those who stop by, hoping either to simply enjoy the music or, in the best of all worlds, be inspired by it.

Regarding the second part of the question, I think Bob Dylan the performer will be remembered as someone with a unique sense of passion and as someone who was the premier songwriter of his era.

BDFC:

What do you think of Bob's last couple of records? Do you have a favorite from the last few years and why?

RH:

I think it is clear that Bob Dylan recaptured his artistry and vision in the series of albums that started with “Time Out of Mind.” I love that album because it gives me the feeling of someone nearing the end of his journey looking back over his life—a bookend, if you will, to his early work, which represented someone just starting his journey. But I also love the sound—the sheer joy of making music—that radiates through the post-“Time Out of Mind” albums. “Love and Theft,” for instance, is joyful enough to make you smile.

BDFC:

When we a nnounced this interview to our Fan C lub members and asked them what they would like to ask you, many of them posed questions regarding Bob's perception of his fans. From what you have observed, how would you describe Bob's relationship to his audience?

RH:

My sense of watching him on stage in recent years is that he (a) is clearly grateful for the loyalty of his fans and (b) that he can best serve his audience by maintaining his independence as a performer rather than simply trying to please that part of the audience that only wants to hear the hits with all the original arrangements. By rethinking the music, he keeps it fresh and meaningful.

BDFC:

If you could choose one anecdote from the time you've spent with Bob that best encapsulates something about his personality or what it's like to be around him, what would it be?

RH:

I have found Bob Dylan to be as fascinating and as complex a person in life as the one you sense in his songs, but he also has very warm, generous side. He has a good sense of humor and a surprising humility.

In the book, I tell about the time I went with Bob Dylan on his first mini-tour of Israel.

Nearly 40,000 fans turned out to see him in a sprawling park of Tel Aviv, many of them holding candles in salute. It was probably the most anticipated concert in the city's history.

Rather than tailoring the material to an audience that had waited decades to hear his early anthems, Bob stuck mostly to newer, lesser-known songs like “Joey” and “Senor.” The fans were disappointed and there was considerable grumbling in the reviews the next morning in Tel Aviv's four largest newspapers.

I had breakfast the next morning with Bob and he asked, “How was the crowd?”

I told him that the audience was glad to see him, but was disappointed that he hadn't done more of his familiar songs. He scoffed. He said he never wanted to let the audience dictate what he should do on stage. I told him I would normally agree, but that this was a special case. This audience strongly identified not only with his socially conscious music, but also with his Jewish roots.

He was quiet for a few seconds, then asked, “What songs do you think I should do?”

I tore a sheet of paper from my notebook and wrote down song titles, starting with “The Times They Are a-Changin'.”

The next night—before 9,000 fans in the scenic Sultan's Pool in Jerusalem—Bob Dylan stepped to the microphone and started singing, “The Times They Are a-Changin'.” He followed with several more songs from my list, including “Like a Rolling Stone” and “Ballad of a Thin Man.” The crowd was ecstatic.

Fifteen years later in Los Angeles, I brought my wife, Kathi, backstage to meet Bob before a concert at Staples Center. I must have seen him a half-dozen times since Israel, but he had never mentioned the piece of paper I gave him I Tel Aviv. When I introduced Kathi, though, Bob smiled and said, “Does your husband have a set list for me tonight?”

BDFC:

When we met Bob he said that reviewers of his shows often, if not always, “get it wrong,” and talked about how they look at the surface and not at substance, missing what's important. As a concert reviewer, what did you do differently in terms of approach and style to win the trust of Bob and others and assure a substantive review?

RH:

I think of my interviews with Bob Dylan as more revealing than my reviews of his live shows and/or albums and my goal in those interviews and profiles is to capture him honestly. When I first started writing for the Los Angeles Times in the early 1970s, I would often read as many interviews with an artist as I could before I met them—and I frequently found I didn't recognize in person the artist I read about in print. That's because writers often injected themselves into the story so much that they became co-stars of the article. In addition, I found many writers tended to dramatize the subject in ways that distorted the artist's personality and/or views.

So my goal was to present the artists—including Bob Dylan—as accurately and as honestly as I could. I wasn't the co-star of the piece. I was just the messenger—between the artist and my readers. And I think the reason I was able to build a good relationship with many of the most respected artists of our times—from Bob Dylan and John Lennon to Bruce Springsteen and Bono—is that they felt they could trust me. In addition, I was interested in these people as artists (their creative processes, their influences, their visions) rather than their celebrity.

BDFC:

What is your personal favorite era of Bob's music?

RH:

I treasure Bob's socially conscious songs and attempts to try to capture the currents of the times, but I think my personal favorites are the love songs, regardless of era---starting with from “Love Minus Zero (No Limit)” and “To Ramona” and going through his catalogue, including such tunes as “Just Like a Woman” and “If You See Her, Say Hello” and “I Believe in You” and so on. There's a brilliant mix between longing and regret that fuses most of the songs with a tension and realism.

BDFC:

How, if at all, do you think the “entertainment media” has changed since you first started ? Have you noticed a shift in interviews and articles wanting more and more of the person's private life, rather than a discussion of their art, or has that element always been just as prevalent?

RH:

The most disappointing change is that so many writers and publications go way, way too far in treating today's celebrity pop artists (from Paris Hilton at one end to the American Idol crowd at the other) as creditable artists rather than mediocre (or worse) record makers. I realize that publications have to write about celebrities in order to draw hits on the website and satisfy the curiosity of newspaper readers in a time when papers are fighting for their survival. But they need to go much further in drawing a distinction between the American Idol crowd and the truly great artists out there.

BDFC:

If you could interview one character from one of Bob's song, who would you choose? What would you ask him or her?

RH:

Someone who intrigues me is the narrator in the song, “Not Dark Yet,” a song on “Time Out of Mind”—someone who is looking back at his life and trying to come to grips with what he sees before the darkness does fall. You feel the chill of last rites in every line of the song, starting with:

Shadows are fallin' and I've been here all day

It's too hot to sleep and time is runnin' away

Feel like my soul has turned into steel

I've still got the scars that the sun didn't heal

There's not even room enough to be anywhere

It's not dark yet but it's gettin' there.

I'd ask him to give me some of his thoughts on the things in life that he found rewarding and what things were essentially a waste a time—and what he might have done different.